History of Kamaiya in Nepal

History of Kamaiya (Bonded Labourers) in Nepal

- Introduction of Kamaiya:

Before knowing about the Kamaiya, there is a need to know the history of Tharu (please study above on the history of Tharu). “Kamaiya” word comes from the Tharu language. Its word meaning in Tharu language is the persons who work hard and a lot called Kamaiya. But the modern meaning of the word Kamaiya is bounded labor. There are different kinds of bonded labor in Nepal. Kamaiya is probably the most exploitative form in the western part of Nepal’s lowland Terai plains. The vast majority of Kamaiya are the indigenous Tharu. The Kamaiya system revolved around a yearly contract made between an agricultural labors and landlord. A Kamaiya would make an agreement with a landowner every Maghi or New Year of the Tharu community. The landlord promised to provide an agreed-upon remuneration usually paid sacks of rice in return for which must work the whole year for the landlord. In practice, the amount received was seldom enough to feed Kamaiya’s family for a year, but they always faced the problem to pay for health treatment and send their children to the school. Whether they didn’t get sufficient remuneration for the work, they were compelled to agree for the landlord’s defined remunerations. Most Kamaiyas own no land themselves, or if they do it is far too little to provide for them. Moreover, most Kamaiyas were already in debt. So Kamaiya use to sign the contract with the landlord or find another landlord willing to take over his debt, effectively buying Kamaiya and his family. When Kamaiya gets to the time of year when his food runs out, or when his wife falls sick, or when his daughter had to marry, or when any of the unusual circumstances that were usual in a human life happens, he use to borrow again from the landlord. And so the loan grows. And when Kamaiya becomes old and cannot work, the loan passes on to his sons or in the name of other family members.

- The path of being Kamaiyas

In the middle of the 19th century the Rana rulers in Kathmandu made in an active economic policy to sell Sal trees of the jungle to the British East India Company to the construction of the railway in India and the Nepal government plan to expansion of arable agricultural field. In 1951, the Government of Nepal enacted a progressive land reform act that centralized non-registered land. The large-scale population shifts happened, it in the region and it was then that the World Health Organization WHO spared large parts of the jungle with DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) in a very successful anti-malaria drive. All of a sudden the deadly anopheles mosquito, that long-time neighbor of the Tharus always troubling but also paradoxically protecting their livelihoods was decimated. The consequent destruction of the jungle and establishment of large scale settlements by hill people accelerated almost overnights. This however, resulted indirectly in the Tharus losing their traditional motherland. Hill people who were better educated, familiar with the political and administrative system, and had connections in government administration, quickly gained ownership of most of the farmland in the region. The Tharus were reduced to tenants working for landlords on land that had previously been their own. In society, they were looked down upon and discriminated against by the high-caste settlers. Their illiteracy and lack of representation in local government offices made it difficult for them to struggle against the new landlords. Many fell into debt and were forced to become bonded laborers, known as Kamaiyas (men) and Kamlaharis (women), who were bought and sold yearly for agriculture and housework. For generations to generations, tens of thousands of families have lived like this despite Nepal’s signature on UN international conventions against slavery.

A Comparative survey in Dang valley, one of the most heavily settled Tharu region, showed the extent of the transformation. In 1912, the great majority of landowners were Tharu. Fifty years later, in the late 1960s, the landowners were mostly settlers from the hills. Eighty percent of the Tharu were tenants and 90% of the landlords they worked for were high caste hill people (McDonough, 1999), initially, accepted the reduction to tenant farmers perceiving it as a continuation of the prior taxation systems in Nepal. Only too late did they realize that the landlord could evict them if they were not legally registered as tenant. Some migrated to the west in search of what remained of the virgin jungle, only to find that similar developments taking place there. Despite the eventual land reform, most of the fields in the western Tarai legally disappeared from under the plows of those who worked them. Families spent lifetimes thereafter wandering from landlord to landlord.

Generations to generations, tens of thousands of Tharu cultivators became bonded laborers who were farming other people’s land. Wives became servants in landlords’ kitchens. And children worked in others’ households until they were old enough to take over their parents’ work. The grandparents’ loss of their land became the grand child’s cursed inheritance, the hole that no amount of borrowing would fill.

Fifty years later, freed Kamaiyas and landlords are coming to terms with this history of displacement. They are discovering that slavery is not just about the work the Kamaiyas do for the landlords, but about the relationship between them, about lower-hood and upper-ness. Not all landlords treat their Kamaiya cruelly. Some Kamaiyas stayed on even if they had no debts. But the Kamaiya/landlord relationship is always experienced as a relationship between inferiors and superiors. It is experienced this way on both sides, by both the Kamaiya and landlord, and the extent to which this socialist of slavery, has written: “What was universal in the master-slave relation was the strong sense of honor the experience of mastership generated, and conversely, the dishonoring of the slave-condition.” (Patterson, 1982)

The Peaceful Kamaiya Freedom Movement

There was a practice to keep slaves by elite groups in Nepali society. The practice of slavery was not acceptable to the progressive people of Nepal at that time which enforced Rana Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher Rana to ban slavery in Nepal in 1925. After the revolution of the 1950s, first time Nepal got the elected prime minister which in 1956, the Government of Nepal signs on the UN convention against slavery to eliminate the slavery system from Nepal At that time the plain area of Nepal covered by dense forests and only the Tharu people resided in this area because other people could not stay for longer due to fear of the Malaria epidemic in the area. The World Health Organization (WHO) started the malaria eradication program in the 1960s to pave the way for the people of Tarai to protect from Malaria. But the eradication of Malaria in the Terai region became averse to the Tharu people’s culture, tradition, systems, and access to natural resources because innocence and lack of awareness and literacy, thousands of Tharu were cheated by the clever new settlers from the Hill areas. The Tharu people forcedly had

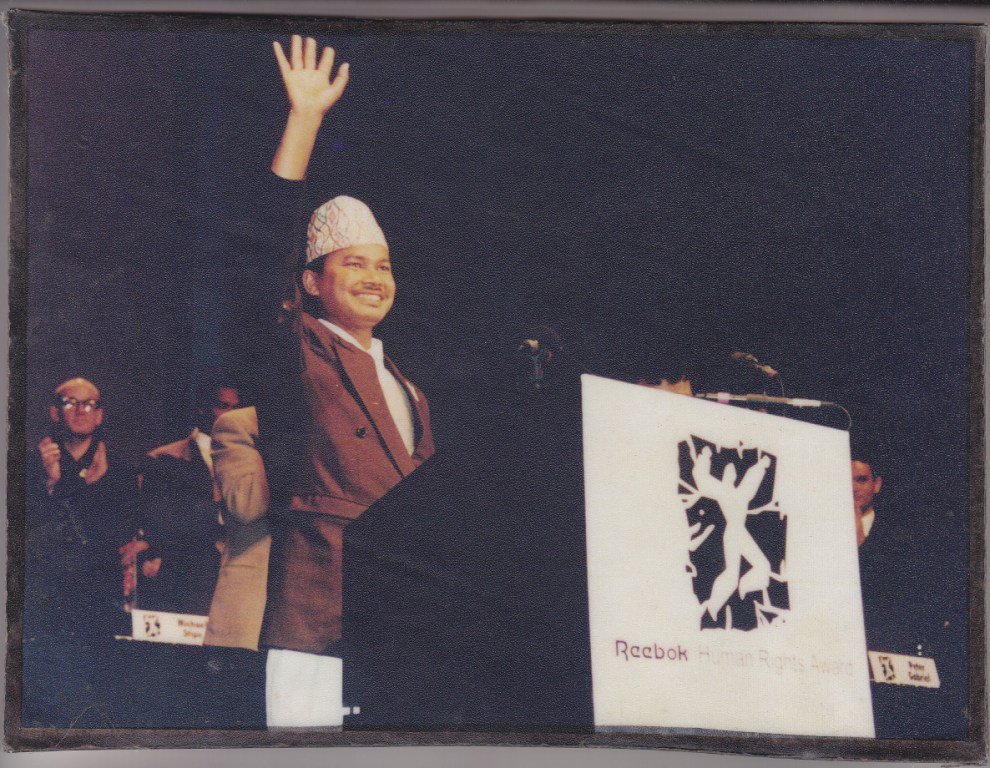

to put their thumbs on the blank paper and legally loosed their property including land. Then, the Tharu people became scarce to food and they compelled to work to new landlords home with minimal labor wage which was not sufficient to them for yearly food security and other needs. Thus, the Tharu people became borrowers and lapsed into debt of landlords who started to keep those Tharu people as bonded laborers (Kamaiya). During the Kamaiya system many Tharu women and men committed suicide and got murdered due to the physical, mental, sexual, and economic exploitation over them. Because of the above-mentioned miseries of Tharu Kamaiya people; since 1985, Backward Society Education (BASE) organizes Kamaiyas and other Tharu people in the western Tarai region for the liberation of Tharu Community from bonded-ness through organizing empowerment campaigning and literacy classes. In 1990, The constitution of Nepal prohibited any kind of slavery or serfdom but the immediate government of Nepal didn’t promulgate any law to enforce the constitutional rights against slavery or serfdom that slavery in the form of Kamaiya became perpetuated until the declaration of freedom of Kamaiya on July 2000. To get freedom from the Kamaiya system BASE led the peaceful Kamaiya movement in coordination with various human rights and social organizations. In 1994, London-based Anti-Slavery International and Kathmandu based human rights organization conducted a study on the status of Kamaiyas in mid and far-western regions of Nepal. They concluded nearly 95 percent of the 300,000 people Kamaiya family members in the region belong to the ethnic Tharu community. BASE and other local NGOs were providing the literacy and legal education classes, Income Generation Activities (IGA), and empowerment campaigning to the Kamaiya people by organizing them to fight against slavery. The events empowered Kamaiya people and aware them on the rights to freedom from slavery, they started to become organized in the groups to fight against Kamaiya practice.

The first time, Nepalu Chaudhary registered the complaint against his landlord in Laxmipur VDC (Village Development Committee) in the Dang district, demanding to fix the minimum wage that he had worked for his landlord. But the landlord refused to pay him minimum wage and grant him freedom from his debt. After this event, Kamaiyas became more aware to seek their freedom from bonded laborers which was spread over the Dang, Banke, Bardiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur districts of western Terai region. Then, on the 18th of January, 2000, Kanchanpur DDC (District Development Committee) reached on an agreement with local landlords who voluntarily released 22 Kamaiya families with Sauki (debt of Kamaiya family) of less than Rs. 15,000. On the 18th of March 2000, Kamaiya of Sankarpur VDC in Kanchanpur district filed the complaint against their landlord. Beneath the hearing of the complaints of the Kamaiya in Sankarpur VDC, Maoist rebellions attacked to the landlord on the same week that displaced the complainers from their village so that the complaints could not reach in the decision. On the occasion of international Labor Day, 1st of May 2000, 19 Kamaiyas filed complaints in Geta VDC in Kailali district against former Minster and landlord, late Mr. Shiva Raj Panta, to pay them minimum wage fixed by the GoN. On the 10th of May 2000, Geta VDC arranged a mediation meeting on the complaints in which 19 Kamaiyas, Journalists, and social organizations working on bonded labor issues participated in the mediation meeting. But landlord Mr. Shiva Raj Pant did not appear before the mediation meeting, so that the Geta VDC could not be able to resolve the case. On May 11, 2000, with the help and co-signature of various organizations the 19 Kamaiyas filed their appeal to Mr. Tana Gautam, Chief District Officer (CDO) of the District Administration Office, Kailali. But, the CDO refused twice to register the appeal. Then, Kamaiyas and supporters of the Kamaiya freedom movement began to protest to the CDO office. On May 16, 2000, the CDO forwarded the appeal to the District Labor Office (DLO). The DLO sent the case back to the Geta VDC. Similarly, on May 21, 2000, 48 Kamaiyas from six VDCs of Kanchanpur district filed a separate complaint in concerned VDC offices demanding freedom from the Kamaiya system. Two days later Parasan VDC issued a freedom certificate to one of the Kamaiyas Mr. Bahadur Rana.

Thus, on May 26, 2000, 4 Kamaiyas from Kailali district traveled to Kathmandu with the Geta VDC chairperson to pressurize the GoN to resolve the Kamaiya issue in Nepal. On May 30, 2000, over 10,000 people demonstrated a rally in Dhangadhi to protest the government’s apathy to Kamaiyas’ issues. On June 8, 2000, three leaders of United Marxist Leninist (UML) of Kailali district liberated their Kamaiyas. After the event, on June 12, 2000; 676 Kamaiyas from five districts filed complaints in their respective CDO demanding freedom from debt bondage, resettlement of Kamaiyas, and government’s protection to the Kamaiyas from the landlord. Then, on July 8, 2000 Kanchanpur Local Government Officials, NGOs, leaders of Kamaiyas agreed to liberate Kamaiyas in the district. Meanwhile, Kamaiyas from 5 districts demonstrated mass protests in Kathmandu to pressurize the GoN to end the Kamaya system from Nepal led by the founder of BASE Mr. Dilli Bahadur Chaudhary. Thereafter, on Monday, July 17, 2000, Land Reform and Management Minister Mr. Siddha Raj Ojha submitted a Bill to the House of Representative, In that Bill, the Cabinet Ministers’ meeting had decided that the practice of bonded labor should be illegal and anybody keeping bonded laborers will be punishable under the law. And the bill was passed by the House of Representatives and the Kamaiya system from the Nepal was ended. After this accomplishment of the Kamaiya freedom movement, 16,000 Kamaiyas attended a victory rally whether there was heavy rainfall on August 6, 2000. Whether, the government freed Kamaiyas, but it was not unprepared for the rehabilitation of around 300,000 Kamaiya people, therefore, the next movement was started for the rehabilitation of Freed Kamaiyas. All the events of the Kamaiya movement from village and district to Kathmandu were led by the level-wise BASE committee, and staff.

Thus, on May 26, 2000, 4 Kamaiyas from Kailali district traveled to Kathmandu with the Geta VDC chairperson to pressurize the GoN to resolve the Kamaiya issue in Nepal. On May 30, 2000, over 10,000 people demonstrated a rally in Dhangadhi to protest the government’s apathy to Kamaiyas’ issues. On June 8, 2000, three leaders of United Marxist Leninist (UML) of Kailali district liberated their Kamaiyas. After the event, on June 12, 2000; 676 Kamaiyas from five districts filed complaints in their respective CDO demanding freedom from debt bondage, resettlement of Kamaiyas, and government’s protection to the Kamaiyas from the landlord. Then, on July 8, 2000 Kanchanpur Local Government Officials, NGOs, leaders of Kamaiyas agreed to liberate Kamaiyas in the district. Meanwhile, Kamaiyas from 5 districts demonstrated mass protests in Kathmandu to pressurize the GoN to end the Kamaya system from Nepal led by the founder of BASE Mr. Dilli Bahadur Chaudhary. Thereafter, on Monday, July 17, 2000, Land Reform and Management Minister Mr. Siddha Raj Ojha submitted a Bill to the House of Representative, In that Bill, the Cabinet Ministers’ meeting had decided that the practice of bonded labor should be illegal and anybody keeping bonded laborers will be punishable under the law. And the bill was passed by the House of Representatives and the Kamaiya system from the Nepal was ended. After this accomplishment of the Kamaiya freedom movement, 16,000 Kamaiyas attended a victory rally whether there was heavy rainfall on August 6, 2000. Whether, the government freed Kamaiyas, but it was not unprepared for the rehabilitation of around 300,000 Kamaiya people, therefore, the next movement was started for the rehabilitation of Freed Kamaiyas. All the events of the Kamaiya movement from village and district to Kathmandu were led by the level-wise BASE committee, and staff.

After the freedom of Kamaiyas, angry landlords started evacuating Kamaiyas from their houses. Some Kamaiyas are beaten and asked to repay their Sauki (debt) to their former landlords. Then, the national/local NGOs and some government line agencies tried to provide shelters to displaced freed Kamaiyas in the temporary settlement camps. Kailali DDC chairman Mr. Narayan Datta Mishra issued a statement that he disagreed with the GoN’s decision to withdrawal of bonded laborer’s debts to landlords. On August 9, 2000, the new Forum for the Protection of Farmer’s Rights filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court demanding government’s compensation for landlords of the Sauki (debts of Kamaiyas) of their freed Kamaiyas. Kailali district’s land reform officer Mr. Maheshwor Niraula estimated that 25 to 40 percent of the Kamaiya registration forms filled by freed Kamaiyas are not Kamaiyas. Till September 7, 2000, there were established 37 temporary settlement camps of displaced Kamaiyas in Kanchanpur and Kailali districts. Ministry of Land Reform and Management (MLRM) spokesperson said that the government plans to provide at least one Kattha of land for each family of former Kamaiyas. But Kamaiya freedom movement actors demanded a minimum of 10 kattha (0.3 hectares) of land should be provided to free Kamaiyas. On September 18, 2000, a high-level government coordination committee announced the plan to implement an emergency food assistance program and to distribute the government’s land to freed Kamaiyas for their sustainable residence. But, on October 24, 2000, dissatisfied Kamaiyas organizations like the Kamaiya Liberation Struggle Mobilization Committee (KLSMC) and Kamaiya Liberation Action Committee (KLAC) decided to launch a new protest campaigns because the government’s efforts to settle the freed Kamaiyas were very slow. Thus, seven thousand Kamaiya from five districts participated in a protest rally and strikes at the government office in Dhangadhi demanding 10 kattha of land for each Kamaiya family on November 24, 2000.

In this protest and strike, 15 Kamaiyas became injured by the police’s attacks to disburse the protesters and strikers. On December 19, 2000, Kamaiyas and their supporter blocked the highway in five districts of south-western Nepal to support their demand for ten Katthas of land to each Kamaiya families. Similarly, the Kamaiyas started to occupy the Forrest land illegally. On January 1, 2001, more than 2000 freed-Kamaiyas living in camps in Kailali district occupied forest land after the KLSMC criticize the government for delaying the land distribution process. On January 9, 2001, Kanchanpur district officials decided to provide 10 Katthas of land to freed Kamaiyas who have more than 5 family members and 5 Katthas to Kamaiya families of less than 5 members. On February 3, 2001, 300 riot police evacuated 7,000 freed-Kamaiyas from the huts made illegally in the land of the government in Bardia district and burnt the huts constructed in the land of the government.

In this protest and strike, 15 Kamaiyas became injured by the police’s attacks to disburse the protesters and strikers. On December 19, 2000, Kamaiyas and their supporter blocked the highway in five districts of south-western Nepal to support their demand for ten Katthas of land to each Kamaiya families. Similarly, the Kamaiyas started to occupy the Forrest land illegally. On January 1, 2001, more than 2000 freed-Kamaiyas living in camps in Kailali district occupied forest land after the KLSMC criticize the government for delaying the land distribution process. On January 9, 2001, Kanchanpur district officials decided to provide 10 Katthas of land to freed Kamaiyas who have more than 5 family members and 5 Katthas to Kamaiya families of less than 5 members. On February 3, 2001, 300 riot police evacuated 7,000 freed-Kamaiyas from the huts made illegally in the land of the government in Bardia district and burnt the huts constructed in the land of the government.

The following is the rehabilitation status of freed –Kamaiya in west Nepal; For effective management of rehabilitation package, it seems that the government of Nepal has made a category of ex- Kamaiya as mentioned below.

- Red card (“A” category): Ex- Kamaiya family who doesn’t have land and house are categorized into “A”.

- Blue card: (“B” category): Ex- Kamaiya family those who are using government or public land but don’t have legally registered land in their name are categorized into “B”.

- Yellow card (“C” category): Ex- Kamaiya families who have maximum 338.6 square meter of land and house in their name are categorized into “C”.

- White card (“D” category): Ex- Kamaiya families who have more than 338.6 square meters land and house in their name are categorized into “D”.

Identity Card Distribution Status of ex- Kamaiya in Nepal

| S.N. | District | # of Ex Kamaiya HHs | Category of identity card provided by Nepal government | |||

| Red card | Blue card | Yellow card | White card | |||

| 1 | Dang | 1426 | 302 | 403 | 397 | 324 |

| 2 | Banke | 2316 | 1118 | 803 | 135 | 260 |

| 3 | Bardiya | 14499 | 6469 | 5082 | 1115 | 1833 |

| 4 | Kailali | 9762 | 3758 | 5217 | 189 | 598 |

| 5 | Kanchanpur | 4506 | 3923 | 495 | 33 | 55 |

| Total | 32509 | 15570 | 12000 | 1869 | 3070 | |

| (Source: Nepal Ex- Kamaiya Education and Poverty Alleviation (NEKEPA) Project completion report March 2016 by BASE). | ||||||

As per the government policy and rehabilitation plan Nepal government has decided to provide full rehabilitation packages to category “A” and “B” ex- Kamaiya only where the number stand to be rehabilitated 27570 ex- Kamaiyas families (please see above table).

Ex-Kamaiya Rehabilitation Status:

| S.N. | District | # of ex- Kamaiya received land by end of Feb. 2016 | # of ex- Kamaiya received their entitled monetary rehabilitation support before project intervention (before 31 Dec. 2012) | # of ex- Kamaiya received their entitled monetary rehabilitation support after project intervention (From Jan.1 2013 to March 2016) |

| 1 | Dang | 705 | 445 | 260 |

| 2 | Banke | 1921 | 901 | 1020 |

| 3 | Bardiya | 10568 | 3586 | 6982 |

| 4 | Kailali | 8602 | 4288 | 4314 |

| 5 | Kanchanpur | 4390 | 2799 | 1591 |

| Total | 26186 | 12019 | 14167 |

(Source: Nepal Ex- Kamaiya Education and Poverty Alleviation (NEKEPA) Project completion report March 2016 by BASE).

The above table shows that total number of 26186 ex- Kamaiyas families have been rehabilitated by Nepal government by end of Feb. 2016.

The above table shows that total number of 26186 ex- Kamaiyas families have been rehabilitated by Nepal government by end of Feb. 2016.

Before NEKEPA project the total rehabilitation number of ex- Kamaiya were 12019 and after the project intervention the number has been significantly increased to 14167. The project has also contributed to increase the number of ex- Kamaiyas for rehabilitation. Out of 27570 ex-kamaiya families, there are 1384 ex-kamaiya families still need to be rehabilitated.